Manon Lescaut

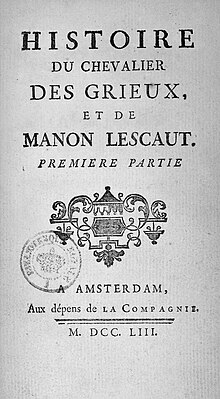

Title page of the standalone 1753 edition | |

| Author | Antoine François Prévost |

|---|---|

| Original title | Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux, et de Manon Lescaut |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 1731 |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | |

Original text | Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux, et de Manon Lescaut at French Wikisource |

| Translation | The Story of the Chevalier des Grieux and Manon Lescaut at Wikisource |

The Story of the Chevalier des Grieux and Manon Lescaut (French: Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux, et de Manon Lescaut [istwaʁ dy ʃ(ə)valje de ɡʁijø e d(ə) manɔ̃ lɛsko]) is a novel by Antoine François Prévost. Published in 1731, it is the seventh and final volume of Mémoires et aventures d'un homme de qualité (Memoirs and Adventures of a Man of Quality).

The story, set in France and Louisiana in the early 18th century, follows the hero, the Chevalier des Grieux, and his lover, Manon Lescaut. Controversial in its time, the work was banned in France upon publication. Despite this, it became very popular and pirated editions were widely distributed. In a subsequent 1753 edition, the Abbé Prévost toned down some scandalous details and injected more moralizing disclaimers. The work was to become the most reprinted book in French literature, with over 250 editions published between 1731 and 1981.[1]

Plot summary

[edit]The seventeen-year-old Chevalier des Grieux, the younger son of a noble family, is on his way to a seminary when he falls in love at first sight with Manon, a common woman on her way to a convent. He persuades her to run away with him, disappointing his father and him forfeiting his hereditary wealth. In Paris, the young lovers enjoy a blissful cohabitation, while des Grieux struggles to satisfy Manon's taste for luxury. He acquires money by increasingly desperate means: borrowing from his unwaveringly loyal friend Tiberge, cheating gamblers, stealing, and murder. On three occasions, des Grieux's wealth evaporates (by theft, in a house fire, etc.), prompting Manon to have sex with a richer man for money because she cannot stand living in penury.

Manon is deported to New Orleans as a prostitute and des Grieux travels with her. They pretend to be married and live in idyllic peace for a while. Des Grieux reveals their unmarried state to the Governor, Étienne Perier, and asks to be wed to Manon. Perier's nephew, Synnelet, sets his sights on winning Manon's hand. In despair, des Grieux challenges Synnelet to a duel and knocks him unconscious. Thinking he has killed the man and fearing retribution, the couple flee New Orleans. They venture into the wilderness of Louisiana, hoping to reach an English settlement. Manon dies of exposure and exhaustion and des Grieux buries her, in the tragic climax of the tale. Heartbroken, he is taken back to France by Tiberge.

Publication

[edit]Prévost likely composed Manon Lescaut in March and April 1731.[2] At the time, he was in Amsterdam, and was writing quickly to satisfy his contract with The Compagnie des Libraires d'Amsterdam.[2] The story was first published as volume VII of his successful novel Mémoires et aventures d'un homme de qualité, and was released with volumes V and VI in May 1731.[3] It was set apart from the other anecdotes in Mémoires et aventures with both a preface and a preamble.[4]

A substantially revised edition appeared as a standalone publication in 1753.[5] This edition claimed on its title page to be published in Amsterdam by the Compagnie des Libraires, but was actually published in Paris by François Didot.[6] In this edition, Prévost modified some of his most sensationalist language, added a new scene with an Italian prince, and rewrote the ending to replace des Grieux's religious conversion with a more secular morality.[6] The 1753 edition also added eight illustrations and an allegorical vignette on the first page.[7]

Style

[edit]The story is narrated by des Grieux, delivered as a long confession to the protagonist of Prévost's Mémoires et aventures.[8] All events are recounted in the first person, and shaped by des Grieux's retrospective self-justifications.[9] The novel does not use quotation marks, even when des Grieux relates what other characters have said, creating "a free movement between direct and indirect speech".[6]

Major themes

[edit]

Tragedy

[edit]The scholar Jean Sgard argues that all of Prévost's writing, including Manon Lescaut, is ultimately about "the impossibility of happiness, the pervasiveness of evil and the misfortune attaching to the passions," all of which lead to "mourning without end".[10] The story is particularly remembered for its tragic lovers, with des Grieux and Manon being compared to Romeo and Juliet and Tristan and Iseult.[11]

Scandalizing immorality

[edit]On the novel's first publication, the characters and their choices were seen as shockingly immoral.[12] Des Grieux's rejection of the priesthood in favor of a sexual relationship without marriage, and his crimes of fraud, challenged readers' expectations of acceptable actions for the hero of a novel.[13] Manon's decision to have sex for money at several points in the novel, and her general taste for pleasure and luxury, also seemed irreconcilable with her narrative role as a sympathetic love object.[13] Both were seen as corrupted characters.[13] The scandal was intensified by the historical setting of the novel: the story is set fifteen years before the year Prévost wrote it, so it takes place during the during the final years of Louis XIV's conservative and orderly reign, rather than during the regency of King Louis XV when stories of corruption would be less surprising.[14]

Social class and money

[edit]The gulf in social class between the noble des Grieux and the common Manon is an obstacle to their love.[15] Des Grieux and Manon struggle to understand each other due to their different backgrounds.[16]

A distinct, and even greater challenge they face is their lack of money.[15] Manon Lescaut is often highlighted as the first French novel to treat money as a major theme.[15][17] Manon begins the novel with a dowry of 300 francs, which is less than a tenth of an ordinary dowry for a woman entering a convent.[18] The annual salary for a servant (Manon and de Grieux each keep one) was 100 francs, while Manon and de Grieux consider a "respectable but simple" annual income to be 6,000 francs per year.[18] The financial gap between the lovers and their servants is large, but the gap between them and their patrons is even larger: two of Manon's lovers offer her 20,000 and 30,000 francs as annual spending money.[18]

The character of Manon

[edit]Since the novel's first publication, substantial critical analysis has focused on the interpretation of Manon's character.[19] Because Manon's words and actions are always related through the filter of des Grieux's restrospective storytelling, readers can speculate about her real thoughts, feelings, and intentions.[20] The earliest reviews in 1733 saw her as a sympathetic victim of her own youthful folly,[21] and the 1753 illustrations reinforced the image of Manon as someone to be loved, pitied, and forgiven for her mistakes.[22] Eighteenth-century readers also saw Manon and des Grieux as helpless, fated to a tragic ending.[23] The crimes of both were equally justified by their love and their financial need.[23]

Manon's reputation began to change in the nineteenth century, as she became a near-mythological figure.[24] Beginning with the opera Manon in 1884, nineteenth-century adaptations characterized Manon as powerfully seductive.[24] Rather than being a simple, lighthearted girl of common birth, she was depicted as either a femme fatale who corrupts des Grieux, or as a hooker with a heart of gold who is redeemed through her death.[24] The literary historian Naomi Segal summarizes this period as one in which most critics "view Manon as if she were a real woman and to heap upon her all the myths which operate within sexual politics in the non-fictional world".[25]

Twentieth-century interpretations tended to see Manon as the victim, not of her own weakness, but of various social systems.[26] Feminist theorists like Nancy K. Miller and Naomi Segal see Manon as a narrative victim of patriarchy.[26] For these readers, it is important to imagine how Manon might have narrated her story differently from des Grieux's version.[26][9] Cultural-historical theorists see the novel as a conflict between aristocratic and bourgeois ideologies; Manon is marginalized by her class, but makes savvy decisions to strategically ensure her survival.[26] Twenty-first century adaptations reinforced a sociological interpretation of Manon's character.[27] Several adaptations translate the story to new time periods and historical situation, in which Manon is always a non-conformist who boldly pursues love despite distadvantaged circumstances.[28]

Male friendship

[edit]Des Grieux's friendship with Tiberge is a noteworthy example of idealized male friendship and male homosocial desire in the eighteenth century.[11] At the time, ethical treatises commonly described true friendship as a source of moral improvement.[29] The prefatory "Foreword to the Reader", which claims to explain and justify the narrative, presents Manon and Tiberge as representatives of passion and friendship, or vice and virtue, who compete for des Grieux's allegiance.[30] The literary scholar Joe Johnson argues that the failure of des Grieux and Tiberge's friendship is a historically important challenge to the legitimacy of male friendship.[31]

Reception

[edit]Manon Lescaut gained popularity gradually.[32] When first published in 1731 as part of Mémoires et aventures, it was not discussed separately from the rest of the novel.[32] Over the next few years, it was increasingly seen as a highlight of that novel.[32] In 1733, the French police seized copies of Mémoires et aventures due to its morally questionable content.[21] This effective ban led to a sudden increase in popularity.[32] As part of this new popularity, Manon Lescaut was printed separately from Mémoires et aventures several times in 1733 and 1734,[33] though these were unauthorized reprints.[21] In 1753, Prévost proposed a high-quality revised edition of Manon Lescaut as a standalone narrative, which appeared in 1756.[34] Both Mémoires et aventures and the standalone Manon Lescaut were reprinted frequently, with twenty editions of the first and eight of the latter appearing between 1731 and Prévost's death in 1763.[34]

The novel saw another dramatic increase in popularity in 1830, when it was adapted as a ballet.[24] Many further adaptations followed, with new reprints of Manon Lescaut each year.[24]

Adaptations

[edit]Dramas, operas and ballets

[edit]- Manon Lescaut (1830), a ballet by Jean-Louis Aumer

- Manon Lescaut (1856), an opera by French composer Daniel Auber

- Manon (1884), an opera by French composer Jules Massenet

- Manon Lescaut (1893), opera by Puccini

- Manon Lescaut (1940), a drama in verse by Czech poet Vítězslav Nezval

- Boulevard Solitude (1952) "Lyrisches Drama" (lyric drama) or opera by German composer Hans Werner Henze

- Manon (1974), a ballet with music by Jules Massenet and choreography by Kenneth MacMillan

- Manon (2015), a musical written for the Takarazuka troupe by librettist/director Keiko Ueda and composer Joy Son

Films

[edit]- Manon Lescaut (1926), directed by Arthur Robison, with Lya de Putti

- When a Man Loves (1927), directed by Alan Crosland, with John Barrymore and Dolores Costello

- Manon Lescaut (1940), directed by Carmine Gallone, with Vittorio de Sica and Alida Valli

- Manon (1949), directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot,[27] with Michel Auclair and Cécile Aubry

- The Lovers of Manon Lescaut (1954), directed by Mario Costa

- Manon 70 (1968), directed by Jean Aurel,[27] with Catherine Deneuve and Sami Frey

- Manón (1986), Venezuelan movie directed by Román Chalbaud, with Mayra Alejandra

- Manon Lescaut (2013), directed by Gabriel Aghion,[27] with Céline Perreau and Samuel Theis

- 3 x Manon (2014) and Manon 20 ans (2017), television miniseries by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade[27]

Translations

[edit]English translations of the original 1731 version of the novel include Helen Waddell's (1931). For the 1753 revision there are translations by, among others, L. W. Tancock (Penguin, 1949—though he divides the 2-part novel into a number of chapters), Donald M. Frame (Signet, 1961—which notes differences between the 1731 and 1753 editions), Angela Scholar (Oxford, 2004, with extensive notes and commentary), and Andrew Brown (Hesperus, 2004, with a foreword by Germaine Greer).

Henri Valienne (1854–1908), a physician and author of the first novel in the constructed language Esperanto, translated Manon Lescaut into that language. His translation was published at Paris in 1908, and reissued by the British Esperanto Association in 1926.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xxiii.

- ^ a b Sgard 1991, p. vii.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. vii-viii.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. viii.

- ^ Johnson 2002, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Scholar 2004, p. xxxi.

- ^ Scholar 2004, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xvi-xvii.

- ^ a b Donaldson-Evans 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. ix.

- ^ a b Johnson 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. x-xi.

- ^ a b c Sgard 1991, p. xi.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xii.

- ^ a b c Donaldson-Evans 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xiv-xv.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xii-xiii.

- ^ a b c Sgard 1991, p. xiii.

- ^ Wyngaard 209, p. 459.

- ^ Wyngaard 2019, p. 460.

- ^ a b c Wyngaard 2019, p. 461.

- ^ Wyngaard 2019, p. 463.

- ^ a b Wyngaard 2019, p. 466.

- ^ a b c d e Scholar 2004, p. xxix.

- ^ Segal 1986, p. xxii.

- ^ a b c d Wyngaard 2019, p. 465.

- ^ a b c d e Wyngaard 2019, p. 467.

- ^ Wyngaard 2019, p. 467-9.

- ^ Johnson 2002, pp. 170–1.

- ^ Johnson 2002, pp. 171–2.

- ^ Johnson 2002, pp. 186.

- ^ a b c d Sgard 1991, p. xxx.

- ^ Sgard 1991, p. xxx-xxxi.

- ^ a b Sgard 1991, p. xxxi.

Bibliography

[edit]- Donaldson-Evans, Lance K. (2010). One Hundred Great French Books: From the Middle Ages to the Present. New York, NY: BlueBridge. ISBN 978-1-933346-22-9.

- Scholar, Angela, ed. (2004). "Introduction". The Story of the Chevalier Des Grieux and Manon Lescaut (Oxford World's Classics ed.). Oxford : New York : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284065-3.

- Johnson, Joe (2002). "Philosophical Reflection, Happiness, and Male Friendship in Prévost's Manon Lescaut". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture. 31 (1): 169–190. doi:10.1353/sec.2010.0009. ISSN 1938-6133.

- Segal, Naomi (1986). The Unintended Reader: Feminism and Manon Lescaut. Cambridge UP.

- Sgard, Jean, ed. (1991). "Introduction". Manon Lescaut. Penguin Books.

- Wyngaard, Amy S. (2019). "Femme Fatale or Feminist Heroine? Interpreting Manon Lescaut". Romance Notes. 59 (3): 459–470. ISSN 0035-7995.

Further reading

[edit]- (in French) Sylviane Albertan-Coppola, Abbé Prévost : Manon Lescaut, Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1995 ISBN 978-2-13-046704-5.

- (in French) André Billy, L'Abbé Prévost, Paris: Flammarion, 1969.

- (in French) René Démoris, Le Silence de Manon, Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1995 ISBN 978-2-13-046826-4.

- Patrick Brady, Structuralist perspectives in criticism of fiction : essays on Manon Lescaut and La Vie de Marianne, P. Lang, Berne ; Las Vegas, 1978.

- Patrick Coleman, Reparative realism : mourning and modernity in the French novel, 1730–1830, Geneva: Droz, 1998 ISBN 978-2-600-00286-8.

- (in French) Maurice Daumas, Le Syndrome des Grieux : la relation père/fils au XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Seuil, 1990 ISBN 978-2-02-011397-7.

- R. A. Francis, The abbé Prévost's first-person narrators, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1993.

- (in French) Eugène Lasserre, Manon Lescaut de l'abbé Prévost, Paris: Société Française d'Éditions Littéraires et Techniques, 1930.

- (in French) Paul Hazard, Études critiques sur Manon Lescaut, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1929.

- (in French) Pierre Heinrich, L'Abbé Prévost et la Louisiane ; étude sur la valeur historique de Manon Lescaut Paris: E. Guilmoto, 1907.

- (in French) Claudine Hunting, La Femme devant le "tribunal masculin" dans trois romans des Lumières : Challe, Prévost, Cazotte, New York: P. Lang, 1987 ISBN 978-0-8204-0361-8.

- (in French) Jean Luc Jaccard, Manon Lescaut, le personnage-romancier, Paris: A.-G. Nizet, 1975 ISBN 2-7078-0450-9.

- (in French) Eugène Lasserre, Manon Lescaut de l'abbé Prévost, Paris: Société française d'Éditions littéraires et techniques, 1930.

- (in French) Roger Laufer, Style rococo, style des Lumières, Paris: J. Corti, 1963.

- (in French) Vivienne Mylne, Prévost : Manon Lescaut, London: Edward Arnold, 1972.

- (in French) René Picard, Introduction à l'Histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, Paris: Garnier, 1965, pp. cxxx–cxxxxvii.

- Naomi Segal, The Unintended Reader : feminism and Manon Lescaut, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986 ISBN 978-0-521-30723-9.

- (in French) Alan Singerman, L'Abbé Prévost : L'amour et la morale, Geneva: Droz, 1987.

- (in French) Jean Sgard, L'Abbé Prévost : labyrinthes de la mémoire, Paris: PUF, 1986 ISBN 2-13-039282-2.

- (in French) Jean Sgard, Prévost romancier, Paris: José Corti, 1968 ISBN 2-7143-0315-3.

- (in French) Loïc Thommeret, La Mémoire créatrice. Essai sur l'écriture de soi au XVIIIe siècle, Paris: L'Harmattan, 2006, ISBN 978-2-296-00826-7.

- Arnold L. Weinstein, Fictions of the self, 1550–1800, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981 ISBN 978-0-691-06448-2.

External links

[edit]- Full texts at Project Gutenberg in the original French and in an English translation

Manon Lescaut public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Manon Lescaut public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Manon Lescaut on World Wide School

- Images from an illustrated 1885 French edition

- (in French) Manon Lescaut, audio version